Enhanced cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT-E) is a specialized, manual-based, transdiagnostic treatment designed to target the mechanisms that maintain all of the eating disorders 1Fairburn, C. G. (2008). Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

It usually requires 18 outpatient sessions, but more sessions may be needed depending on the nature of a patient’s illness.

CBT-E has also been successfully adapted for inpatient and group settings and has recently been translated for delivery through Internet- and app-based mediums.

I want to use this article to discuss CBT-E in some detail. In particular, I want to focus on describing the underlying theory of CBT, how CBT-E is structured, what the research says about CBT-E and some important limitations to this treatment.

Let’s get stuck in.

Table of Contents

The Theory Behind CBT-E

The theory behind CBT-E serves the foundation for the specific treatment strategies implemented.

CBT-E is based on a transdiagnostic maintenance model of eating disorder psychopathology that has received a lot of empirical support 2Pennesi, J., & Wade, T. D. (2016). A systematic review of the existing models of disordered eating: Do they inform the development of effective interventions? Clinical Psychology Review, 43, 175-192.

According to this model, at the core of all eating disorders is a dysfunctional self-evaluative system. In other words, whereas most people evaluate their identity through a variety of life domains, like work, relationships, education, sporting ability, people with eating disorders tend to evaluate their self-worth almost entirely on their weight and shape.

This overvaluation of weight and shape is the core psychopathology responsible for driving many of the clinical features we see in the eating disorders.

One direct expression of this overvaluation of weight and shape is extreme dietary restraint, which involves multiple strict and demanding food rules that dictate what, when, and how much one is “allowed” to eat.

Common food rules we hear about are:

- Not eating carbs after dark

- No eating after 6 PM

- Not allowing yourself processed foods

- Eating fewer than 1,521 calories per day – no more, no less.

Because of these persons’ regimented thinking patterns, any breaking of these food rules (which, let’s face it, is almost inevitable given how extreme they are) is interpreted as a failure in self-control.

This perception of failure is the mechanism that tends to induce an episode of binge eating (because, what-the-hell, the diet is ruined anyway, so you may as well go all out now while you have the chance?!)

After a binge, some people practice purging as a way to counteract all of the calories consumed, through methods like self-induced vomiting or laxatives.

The guilt, shame, and anxiety associated with binge eating only serve to intensify the overvaluation of weight and shape, thereby leading to an even more vicious cycle.

It should be noted that, in a subset of people, other mechanisms are also operating to maintain this cycle, such as clinical perfectionism, core low self-esteem, interpersonal difficulties, and mood intolerance. These are also a target for treatment if needed.

Ultimately, CBT-E is concerned with breaking this cycle down.

To do this, it utilizes a range of different cognitive and behavioral strategies that help the person stop the regimented dietary practices and place less importance on their weight and shape.

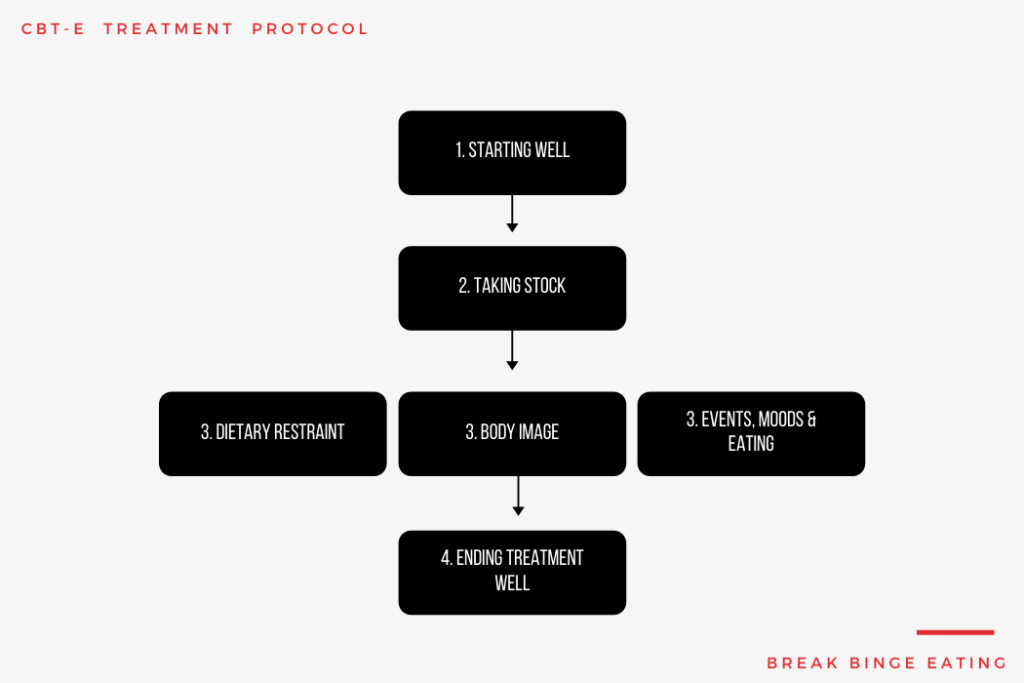

The Treatment Protocol

Stage One : Starting Well

Stage one, which involves 8 sessions held twice weekly over 4 weeks, aims to engage the patient in treatment and change, to derive a personalized formulation (case conceptualization) with the patient, to provide education about treatment and the disorder, and to introduce and implement 3 important procedures: self-monitoring, weekly weighing and regular eating.

The changes made in this first stage of treatment form the foundation on which other changes are built.

Stage Two: Taking Stock

Stage two is a brief transitional stage that generally comprises 2 sessions.

While continuing with the procedures introduced in Stage one, the therapist and patient take stock and conduct a joint review of progress, the goal being to identify problems still to be addressed and any emerging barriers to change, to revise the formulation if necessary, and to design the third Stage.

In Stage two, there is an opportunity to discuss whether one of the four core maintaining mechanisms (perfectionism, low self-esteem, interpersonal problems, or mood intolerance) are obstructing change and hence need to be addressed.

Stage Three: Address Key Processes

This is the main Stage of treatment that consists of 8 sessions.

Its aim is to address the key processes that are maintaining the patient’s eating disorder. The mechanisms addressed, and the order in which these are tackled, depend upon their role and relative importance in maintaining the patient’s psychopathology.

Key treatment strategies designed to target the overvaluation of weight and shape include activity scheduling, self-monitoring of body checking and avoidant behaviors, body exposure, and psychoeducation.

The key treatment strategy designed to target extreme dietary restraint includes exposure and response prevention, where the person faces up to their fear of certain foods.

Stage Four: Ending Well

Stage 4, which involves 3 sessions, is concerned with ending treatment well.

The focus is on maintaining the progress that has already been made and reducing the risk of relapse.

The therapist and patient jointly devise a personalized plan for the following few months until a post-treatment review appointment (usually about 20 weeks later).

Is CBT-E effective?

We’ve provided an overview of CBT-E and it’s protocol. The big question, then, is whether CBT-E works?

Let’s dive into some key facts about CBT-E based on the current research evidence.

CBT-E results in quick change

CBT-E produces its effects much quicker than other specific psychological treatments.

18 sessions of CBT-E produced the same effects as one year of interpersonal psychotherapy and two years of psychoanalytic psychotherapy 3Poulsen, S.. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of psychoanalytic psychotherapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 109-116. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121511.

The benefits of CBT-E are sustained

Many people who recover or improve from 18 sessions of CBT-E continue to experience improvements in one and even 2 years after treatment ends 4Poulsen, S.. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of psychoanalytic psychotherapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 109-116. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121511.

CBT-E can work well for younger people

40 sessions of CBT-E for adolescents with anorexia nervosa resulted in a 96% remission rate in a small pilot study 5Dalle Grave. (2013). Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: An alternative to family therapy? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51, R9-R12.

CBT-E can lead to recovery

Around 45% of people make a full recovery with just 18 sessions of CBT-E 6Fairburn, . (2015). A transdiagnostic comparison of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) and interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 70, 64-71.

CBT-E has much broader effects

People who receive CBT-E usually experience significant reductions in depression and anxiety, as well as profound improvements in their quality of life 7Wonderlich, S. A., Peterson, C. B., Crosby, R. D., Smith, T. L., Klein, M. H., Mitchell, J. E., & Crow, S. J. (2014). A randomized controlled comparison of integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) and enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT-E) for bulimia nervosa. Psychological medicine, 44, 543-553.

Recovery doesn’t depend on your eating disorder

Recovery rates are roughly the same whether you’re suffering from anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or an other specified feeding or eating disorder [re]Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., Doll, H. A., O’Connor, M. E., Bohn, K., Hawker, D. M., . . . Palmer, R. L. (2009). Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: A two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166, 311-319[/ref].

Certain people may respond better to CBT-E

There is evidence suggesting that people with core low self-esteem will benefit more from CBT-E than from other types of psychological treatment 8Cooper, Allen, E., Bailey-Straebler, S., Basden, S., Murphy, R., O’Connor, M. E., & Fairburn, C. G. (2016). Predictors and moderators of response to enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of eating disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 84, 9-13.

Limitations of CBT-E

It is important to point out that CBT-E is not a panacea; there are still a number of limitations to CBT-E that need to be rectified through additional clinical and research work.

Let’s turn our attention to some key limitations to CBT-E;

- CBT-E doesn’t work for everyone – around 50% of people do not fully recover from CBT-E, and even some people show no improvements.

- Around 25% of people drop out prematurely from CBT-E due to dissatisfaction 9Linardon, J., Hindle, A., & Brennan, L. (2018). Dropout from cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51, 381-391.

- CBT-E does not pay close attention to other relevant maintaining factors, like food reward expectancies, shame, and trauma.

- CBT-E may be too confronting for people because it encourages them to directly confront their fears, anxieties, and beliefs.

- CBT-E does not devote much time or attention to the multiple comorbidities experienced by people with eating disorders.

- We are still unsure whether CBT-E works for different ethnic, racial, gender, and economic groups.

References

Leave a Reply